Specifically, she found significant increases pre to post on a number of key indicators of social and emotional well-being:

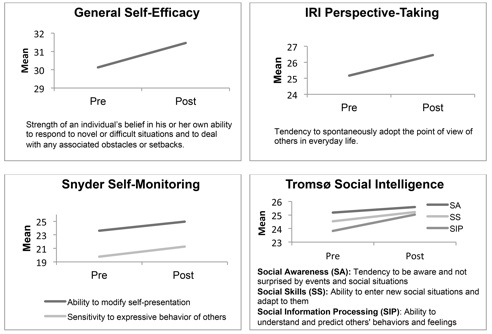

- Tromso Social Intelligence Scale: There were significant gains on two of the three sub-scales of the Tromso social intelligence scale: Social skills and social information processing (Understanding others).

- Snyder’s Self-Monitoring Scale: There were significant gains in two factors underlying the revised version of Synder’s Self-Monitoring Scale: Sensitivity to others’ emotions and Ability to modify one’s own behavior when socially appropriate (scales renamed here for ease of interpretation).

- Bagby et al’s (1994) Toronto Alexithymia scale. There were significant reductions in alexithymia following the intervention.

- Salovey’s TMMS-24 Scale: From pre to post, students reported greater emotional intelligence on the Salovey, et al. Trait Meta-Mood measure.

- Davis’s (1983) Empathy Scale. The sub-scale which measured cognitive empathy, Perspective Taking, improved, pre to post., overall, as predicted. There was no change in emotional empathy, as expected.

- Self-efficacy for social relations, developed by Gonzales 92013) increased from pre to post across the whole sample, with the exception of men who reported an avoidant attachment style.

- Ryff’s Wellbeing Scale: Psychological wellbeing improved significantly from pre to post, as assessed by Ryff’s 42-item measure of well-being.

- Attachment Style: Approximately 75% of the sample were securely attached, 15% showed avoidant attachment, and 10% anxious attachment style based on the Hazan & Shaver’s (1987) Attachment Questionnaire (AQ). Securely attached participants reported higher scores on social intelligence sub- scales, self-monitoring, emotional intelligence and well-being. Comparing the three groups in their changes from pre to post intervention revealed significant differences on two of the study outcomes. As hypothesized, there was greater improvement in social skills for the two groups of insecurely attached participants following the program. There was also evidence of greater improvements in well-being for those insecurely attached. A significantly greater change pre to post in positive social relations (a Ryff’s well-being sub-scale) for those insecurely attached was responsible for the differences in program impact on well-being. There were no differences in program impact on emotional intelligence (all groups improved), or on Self-Monitoring when comparing securely to insecurely attached.

In none of the comparisons did the program make matters worse for a sub-group. The significant effects of attachment style on program impact, when found, were due to those insecurely attached participants showing gains that reduced the difference between their social intelligence at pretest and the social intelligence of those securely attached.

In our view, attachment style, though considered by some a stable trait, can be modified. To examine that hypothesis, the Hazan & Shaver’s Attachment Scale was also administered both pre and post. The program significantly shifted the participants’ styles toward more secure attachment overall at post-test.